Dunay mga sugilanon nga magbilin gayod og marka sa atong hunahuna ug kasingkasing. Uban niini daw nahisulat lang sa hangin apan duna gayoy mga maayong manugilon nga sa kayano nilang mosulat, daw nakauban ta sa ilang panahon ug makadayon sa ilang panimalay.

Sama pananglit niining magsusulat nga nagtubo sa Cordova diin tataw kaayo ang kabugnaw sa atabay sa iyang mga sugilanon. Kusog ang tubod sa iyang mga sugilanon ug yano niya kining napaambit pinaagi sa inahang dila. Sa unang basa sa Mga Awit sa Atabay, ang iyang hinugpong sugilanon, daw nagbasa ka og sugilanong pambata apan makatagbaw gayod ang gilawmon sa pagtulun-an.

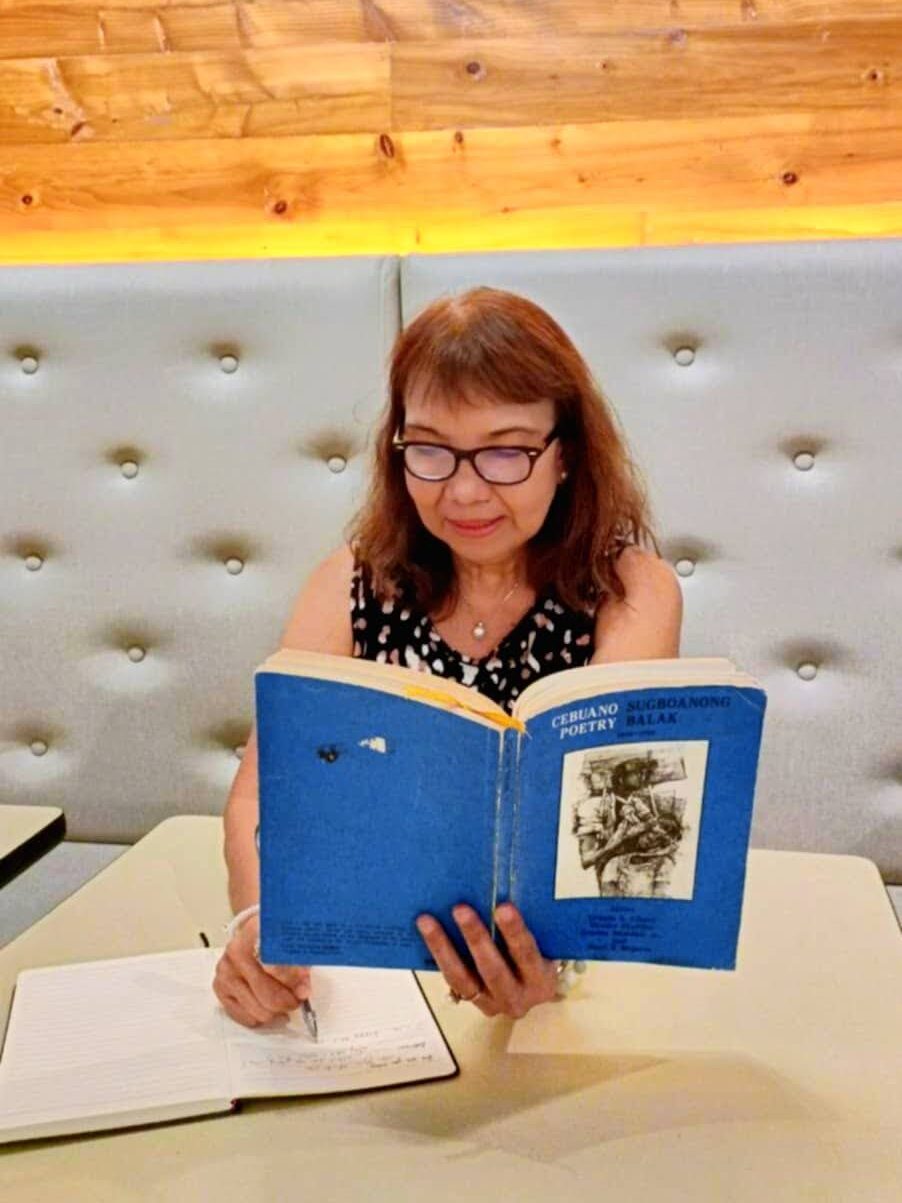

Nahatagan kitag higayon nga mahinabi si Ms. Lilia Tio, ang magsusulat nga nipadayon nato sa panimalay sa iyang panumdoman pinaagi sa iyang mga sugilanon.

Unod sa Pakighinabi:

Jae Magdadaro: Maayong buntag, Ms. Lil. Ako diay si Jae, ang imong higala nga panalagsa ra mangutana nimo kabahin sa panulat apan hagbay ra kong buot mangutana nimo niining mga mosunod. Seguro, dili lang tungod kay higala ta, kon dili, usa ko sa mga nalingaw kaayo sa imong mga sinuwat. Unta mahatagan nimo og gamayng panahon ang mga mosunod nga mga pangutana: Unsa ang “typical writing day” alang nimo? Unsa bay mga paborito nimong kaonon samtang nagsulat?

Lilia Tio: Wala koy typical writing day. Kana lang dunay rason nga mosulat. Pananglitan naay creative writing workshop, o naay poetry reading where one has to read a fresh work, o kanang dunay akong gihangad nga manunulat nga moingon “ayaw biyai ang pagsulat kay maayo kang mogamit sa Cebuano language.”

Sa una, abtik kong mosulat, katong nagtudlo pa ko sa unibersidad kay dihay panahon nga nangulo ko sa Creative Writing Program sa UP Cebu. I had to write, or I had no right to head the program. Some writings got good feedback when critiqued; got published in Bisaya magazine when submitted. When I retired, the urge to write also quieted down. The drive had diminished. I got caught up in renovating the house, maintaining it, getting involved in many church activities, teaching grammar to Scalabrini seminarians. Then the feeling set in that I’m no writer. The writers I know would set aside time to write, write, write; I didn’t. Then when I got to read some creative work and feel I should be writing again – abli dayon kog laptop, nya kaon-kaog mani. But this is occasional and non-regular. And the writing I produced, they were okay but not good enough.

Jae: Sa Mga Awit sa Atabay, tataw kaayo ang kinabuhing yano sa dapit nga duol kaayo sa kinaiyahan, unsa sab ang imong proseso sa pagsulat niini? Naka-impluwensya ba ang imong mga kasinatian sa imong mga gisulat? Duna bay magsusulat o tawo nga may impluwensiya sa imong pagsulat?

Lilia: Sa kadtong nagresearch kos mga karaang Cebuano writers for my Master’s thesis in Literature (Barrio and City Representations in Cebuano Fiction:1925-1930), one writer stood out, si Marcel Navarra. Paborito niyang sulaton ang kinabuhi sa Tuyom, Carcar sa mga yanong tawo: adunay nag-ila-id sa kalisod, nabiktima sa gubat, nakasinati og senswal nga pagbating mabatyagan sa hapit nang maulitawo – naay lingaw, subo, makahinuklog, makagitik ug buhi kaayo ang mga nagtawo sa iyang sugilanon. His Cebuano vocabulary is rich, textured, colorful, apt, and life-giving. His stories haunted me for some time: Paghigmata, Ang Hunsoy Sungsongan Usab, Ug Gianod Ako, and there’s another one of which title I have forgotten. According to my favorite literature professor and National Artist Resil Mojares, “makalaway ang Cebuano ni Marcel Navarra.”

Jae: Giunsa nimo pagpalambo ang imong tingog o ang tingog sa imong mga karakter, sama sa mga nasulat nimo sa Mga Awit sa Atabay?

Lilia: When I wrote my first short story Sapatos, I did not have a clear direction of where it was going. I just wanted to write about and follow this free-spirited barrio girl at a time when barrio life was young, pristine, innocent, fun-filled and pregnant with romance. And the Cebuano language gave life to the girl and the barrio – flowing, spontaneous, fertile – where the Cebuano language’s soil would keep on unearthing, without fail, the words I wanted and how I wanted them to speak for the story and the characters. These words would just pop out in my head, spontaneously. As the scenes paraded before my mind, words came to breathe life into them. At the same time, the ears were alert to the rhythm, the flow of the words as they were spoken, or gave life to situations. Rereading my work, I get to see how my use of Cebuano language would veer towards naturalness, simplicity, and smoothness. I cannot stand artificiality in syntax where diction is awkward, and the effect forced.

I heard it said that language is the fingerprint of voice, that voice lives in diction, syntax, rhythm, and tone. To illustrate one instance, Antonia who is the main character of the story Sapatos is innocently funny as well as self-unconsciously playful. I wanted to give life to this through a picnic scene under the mango tree with her friends and the dialogue that ensued:

“Hoy, Tonying, nganong misugot ka man? Gusto sab ka niya no?” panudya ni Laling samtang nagpiknik mi ilawom sa punoan sa mangga. Gidala nako ang bahaw sa balay, minantikaang isda pod ang kang Pauling, ug putpot nga bulad nga gihumol sa siniliang suka ang kang Laling

“Hala ka, sakit ra ba kuno na (minyo, italics mine); magdugo na pud kuno ka,” panghadlok ni Pauling dayong hungit sa bahaw.

“Naunsa man mo?” matod ko nga naghubit sa putpot. “Wa mo kakita nga misugot ko kay nahuwasan ko nga wala ko malatigo ni Tatay ug wala ko ipadakop. Ug labot pa, dili na siya kahilabot nako. Hadlok man siya sa akong kumo. Unya, molarga sab dayon siya. Di ba kanang taga barko pirme lang wala, busa mora lang gihapon og wa ko maminyo. Unya pa gyod, pag-umangkon na ko ni Nang Andika, busa ato na ang bayabas, he he he”

And the voice grew organically from Antonia’s character, her behavior, mischiefs, her childishness until, with her capacity for reflection, she was eventually pushed towards the threshold of awakening. At some point, early in the story, her character shook free from my grip, as she responded to the situations springing from the story. She lives in the tone, rhythm, diction, syntax of the language that both gave her life and defined her. And all I did was unleash her.

I should say, ang pagpalambo sa Tingog sa akong mga sugilanon nahimo nako diha sa pinong pagpamati unsay haum nga tono sa lain-laing karakter diha sa dialogo; kon magsaysay – sa pagpahimutang sa mga pulong nga hapsay sa akong paminaw, ug paglikay sa pagbutang og daghang mga pulong nga walay kapuslanan ug makapayabag sa ritmo ug makapa-untol sa dagan sa hunahuna sa nagbasa. In short, the sights in my mind are translated into harmonious sounds in the use of language.

Jae: Unsa bay mga teknik sa pagsulat nga imong gigamit sa pagmuna sa mga sugilanon sa “Mga Awit sa Atabay?” Giplano mo ba daan ang direksyon sa imong mga sugilanon o nigawas lang sila samtang imo nang gisulat?

Lilia: I had so many materials in my head gathered from childhood experiences in Cordova, stories my mother and aunts told me about things and people, their ideological beliefs, the baths at the well, arranged marriages in the past, weddings of relatives and the corresponding rituals I witnessed, the carromatas that ply the unpaved road, the haranas and crushes I experienced, the stories shared on moonlit nights: adultery in marriages, corrupt barangay captain, teacher selling wares, etc;. And the mind and heart worked together to weave these experiences into my stories. Just like in cooking, after the main ingredients were thrown into the pan, dashes of wit, humor, irony, metaphor, and other tools of writing would just come and position themselves in their rightful place.

It was also important that I determined first the direction of my stories: stories in the barrio where the well is ever present in the setting, hence the title of the collection, Mga Awit sa Atabay. The well provided a creative compass in steering the stories.

Jae: Unsa ang papel sa rebisyon sa proseso sa imong pagsulat? Unsa sab nga sugilanon ang pinakadali ug ang pinakadugay nimong nahuman pagsulat?

Lilia: Malingaw ko sa rebisyon. Ganahan ko inig balik na nakog basa ug makita nako nga naay yabag sa tono sa pahimutang sa pulong, o diba naay nayabag nga gipadulngan ang mga hitabo sa sugilanon o kaha nisimang ang point of view. This is where I checked my stories for coherence, unity in plot, sentence sense, and concretization of the story – the dramatization of events using dialogue, concrete details and seeing to it that I was not just telling but really describing, dramatizing. And spotting the flaws and correcting them, ganahan ko kay makutaw akong utok. I enjoyed revising.

I wrote Sapatos, my first short story, flowingly. It was the easiest and most enjoyable to write. I love Antonia, the central character. She brought out the childlikeness, the innocence, the pertness that’s in me even at this age, hahaha. And when I had to expand it to meet the required length for a Palanca short story, I was so excited to be able to bring in the rituals of a wedding I witnessed in Cordova in the olden days, embellished it with Antonia’s cheekiness, and the bride’s carromata ride together with her bridesmaids. How organic and natural all these materialized in the story.

Revising Mga Guba sa Balay challenged me. I decided to venture on a subject, marital adultery, when I read Alice Munro’s stories. I was in the US at that time staying in this isolated house of my friend in the middle of a big meadow with no neighboring house in sight, and I felt isolation and intense loneliness. And in one of Munro’s stories, a married woman committed adultery senselessly. So, I decided to dare myself as a writer to write on a subject that I’m not comfortable with. When I let my nephews read the draft of the story, they wanted me to be bolder. They challenged me not to be sanitary in my description, but I said no. I strongly felt that doing so would compromise the integrity of my story. And how to bring back the wife out of her infidelity, lay my great difficulty. I had to struggle on how to pull off this intention without being preachy or didactic. I suppose I was saved from didacticism by my dramatization of the wife’s wrestling with her conscience which was organic and realistic.

**

Leave a Reply